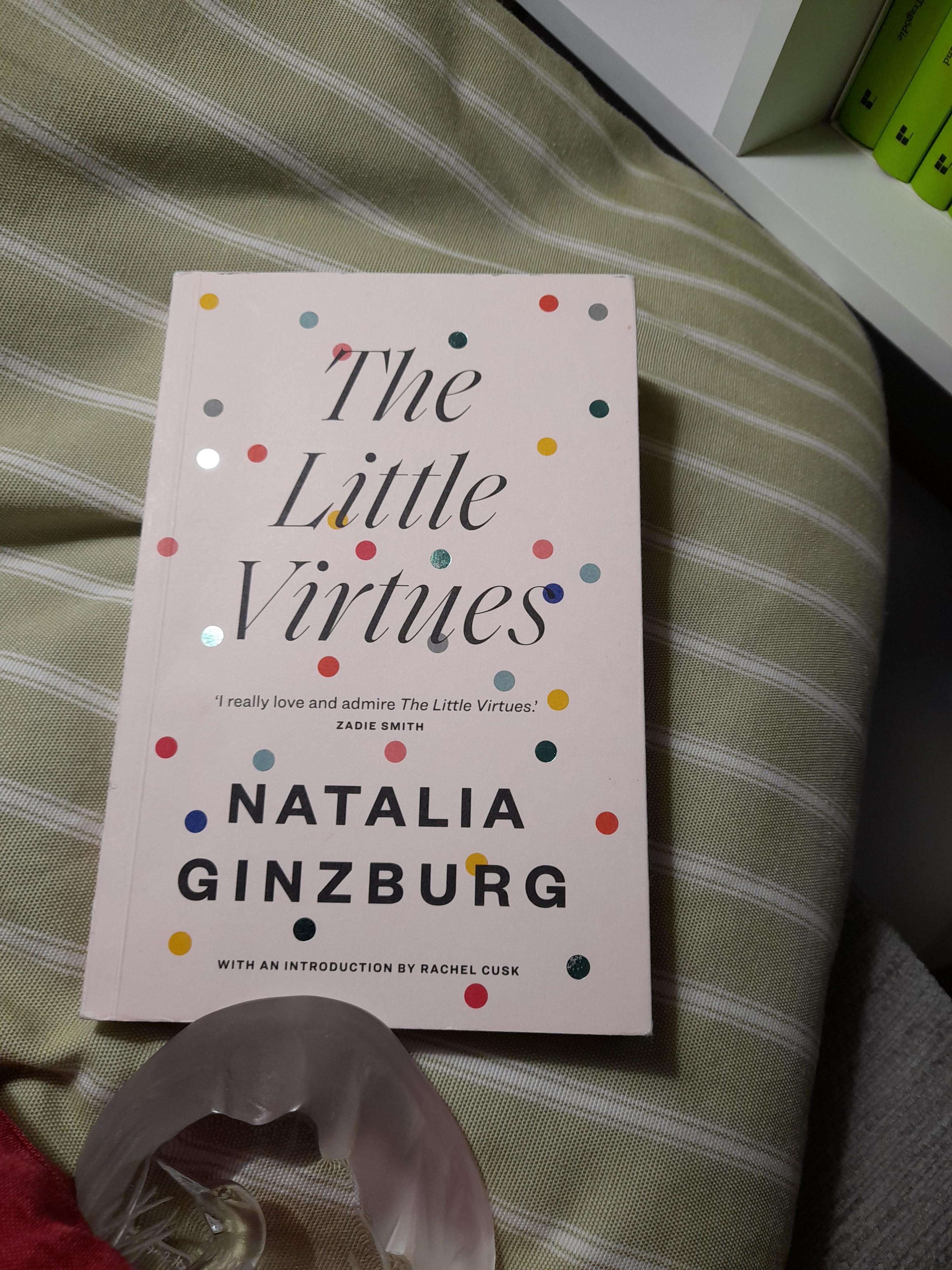

The Little Virtues by Natalia Ginzburg

I say ‘thoughts’ but what I really mean is perhaps feelings. I read very little non-fiction and when I occasionally do, it is in the form of news (sparingly), essays or once in a long while, a biography. Apart from news, it is important to me that any lengthy fiction or non-fiction I read makes me ‘feel’. And man, did the essays in The Little Virtues make me feel! It shouldn’t anymore, but it remains a wonder to me how similarly human we all are at our most basic level, no matter what space and time we inhabit or occupy. These Essays are raw, intimate and full of self-discovery on what it means to be human. Here are a few thoughts on some of my favourite essays:

England: Eulogy and Lament & La Maison Volpe

I thought this was hilarious and but at the same time packed with sober truths about an immigrant’s relationship with their host country. What struck me was how similar some thoughts and feelings were to what I have personally experienced being an immigrant in Europe, though our backgrounds could not be more different. She extols the ordered beauty of England compared to that of Italy, but laments its lack of warmth in interpersonal relationships, the bland food and unimaginative clothing and lack of style.

My Vocation

Ginzburg ruminates of her ‘vocation’ meaning her writing. I especially identify with her thoughts on how our personal happiness or unhappiness, or what she refers to ‘our terrestrial condition’, has the power to impact our creative process(es).

Silence

Ginzburg writes, ‘The silence with ourselves is dominated by a violent dislike for our own existence, by a contempt for our own soul which seems so vile that it is not worth speaking to’. She writes of two kinds of silence; silence with oneself and silence with others. Throughout the essay, silence becomes a synonym for various conditions such as loneliness, depression, guilt among others.

Human Relationships

How does the way in which we relate to others, from infancy to old age, evolve? In this essay, Ginzburg lays out her personal emotional development from childhood through teenagerhood to early and late adulthood, and how her relationships from parents to early friendships impacted that and in return how that influenced her relationships with her family, her children, her friends and the greater community. On children she writes ‘We did not know that there could be such fear, such frailty, in our body: we never suspected that we could be so bound to life by a chain of fear, of such heart-rending tenderness. - the baby in the pram which we are pushing is so small, so weak, the love which binds us to him is so painful, so frightening!’

The Little Virtues

How do we decide what virtues we teach our children? Ginzburg makes a case for prioritising the big virtues; Not thrift but generosity and an indifference to money, courage in place of caution and a contempt for danger, frankness and a love for truth in place of shrewdness, love instead of tact, a desire to be and to know instead of a desire for success.

I loved how generously Ginzburg shares intimate thought processes that we all perhaps have but do not have the courage to articulate them even to ourselves. It is worth mentioning that almost all essays are written with the backdrop of the second world war, escaping the national socialists to Italy, the losses that her family incurred and how all that changed her.